Hope and Charity Book

A History of Catholicism in Thunder Bay

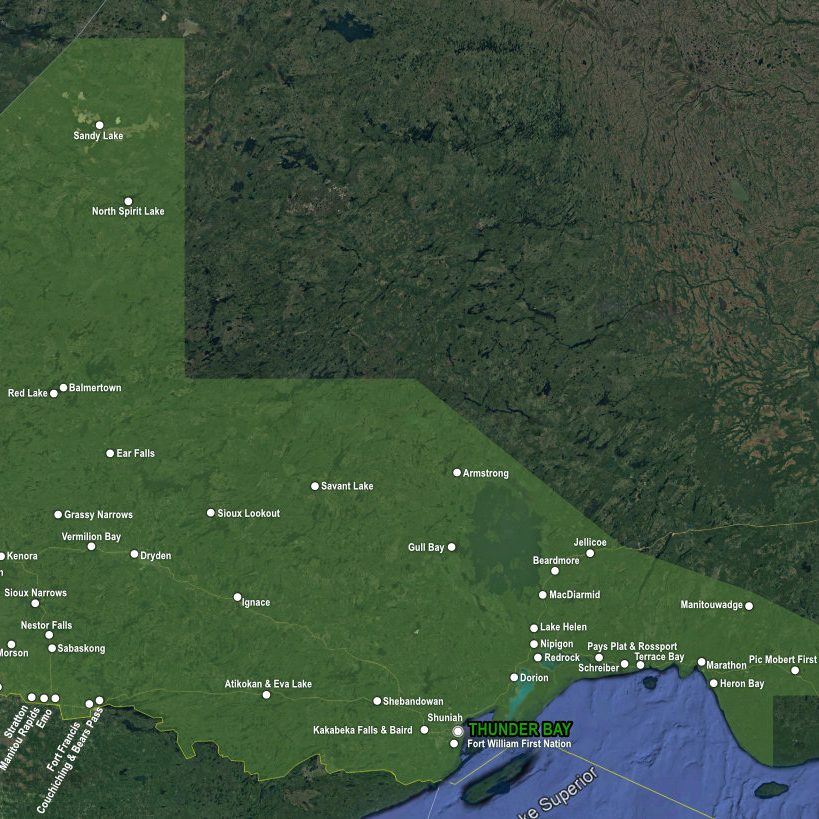

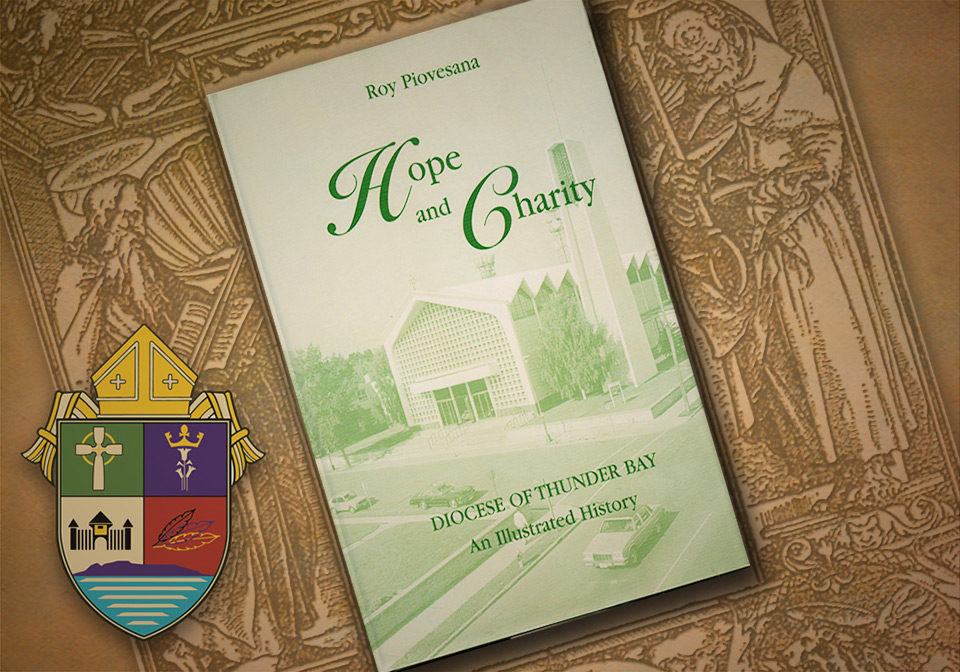

The exciting history of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Thunder Bay has now been published in one volume. The launching of Hope & Charity: An Illustrated History of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Thunder Bay has been timed to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the diocese.

In 328 pages of readable and informative text, author Roy Piovesana tells the interesting story of the Catholic Church in Northwestern Ontario, beginning in the 1890s. From the establishment of the first parishes to the celebration of World Youth Day in the summer of 2002 - it’s all here, presented in an engaging manner, with many colour photographs and graphics.

The book documents, for the first time, the origins and development of the major Roman Catholic parishes in Northwestern Ontario, including the Polish, Italian, and Slovak churches in Thunder Bay. It includes a full chronology of leading events, and a necrology.

Historian Roy Piovesana is the archivist for the Diocese of Thunder Bay. He is also the author of Robert J. Manion: Member of Parliament for Fort William, 1917-1935, St Dominic Parish, 1912-2012 (with Diane Piovesana) and most recently Italians of Fort William’s East End, 1907-1969. He is a past-president of the Thunder Bay Historical Society and the Thunder Bay Art Gallery and was made a Fellow of Lakehead University in 2015.

Hope and Charity may be purchased (hardcover $20) at the Catholic Pastoral Centre (order by phone calling 807-343-9313) or at the Thunder Bay Museum, 425 Donald Street E.

Price is $20 for softcover or hardcover.

Forward by Most Reverend Frederick J. Colli

My dear friends,

The publication of a diocesan history is truly an important event in the life of the faith family. This publication for the Diocese of Thunder Bay is the fulfillment of a long awaited desire beginning with Bishop E.Q. Jennings. As our history unfolded, each bishop expressed a desire for a publication of the life of the church in northwestern Ontario and how our faith was spread in the region beginning with the missionaries and continuing with the service of the diocesan clergy and many religious communities.

I am very pleased that this dream is now a reality and that each of us, through this book, can give thanks for the courage, generosity, and determination of those who have gone before us. In particular, I wish to note the dedication and strong leadership that was shown by Bishop E.Q. Jennings, the first bishop our diocese. In his wisdom and insight, he was able to carve out and organize our diocesan church as we know it today. Building on his initiatives, Bishop Gallagher and Bishop O'Mara also added to our history in significant ways.

As we look to our past and give thanks for the work and goodness shown, we cannot but also sense an obligation in each of us to continue and build the kingdom of God in our area. It is not an easy task. As our leaders in the past, struggled to do what was best for the Church, we took take up the challenge to continue this building in our own way, by the generous sharing of our gifts and talents for the good of the Church and society.

Along with the establishment of many parishes and missions to serve the spiritual needs of all the people of our area, there were many significant developments in the areas of Catholic education, health care, and social services. The prompting of the Gospel and it's message from the Lord, were the inspiration for many of these developments. Let us together continue this noteworthy tradition and build on these strong foundations.

I would like to thank all who contributed to the publication of this volume, and I am especially grateful to the author, Roy Piovesana, our diocesan archivist/historian. May our history inspire us to seek God's help and grace as together we continue the journey of faith in northwestern Ontario.

Excerpts from Hope and Charity

For over fifty years the Mission de L’Immaculée Conception on the Fort William Indian Reserve was the cradle of Roman Catholicism in the region north of Lake Superior. It was established in July 1849 by two French Jesuit missionaries, Father Pierre Choné (1808-1879) and Father Nicolas Frémiot (1818-1854) on the left bank of the Mission River at its junction with the Kaministiquia River. A year earlier they had settled temporarily at a spot on the Pigeon River (which formed part of the international boundary between British North America and the United States) with the intent of establishing a mission there.They were drawn to the Kaministiquia River site because the land was more arable and there were greater opportunities to convert Indians to Roman Catholicism. Until its demise in 1906,

it was the base and headquarters for Jesuit missionary activity extending over an immense area from Grand Portage and Grand Marais on the northwestern shore of Lake Superior in the United States to White River, 320 km east of Fort William. Equally important, the Church of the Immaculate Conception on the Fort William Mission served the spiritual needs of Indian and European Roman Catholics on the Fort William Indian Reserve and in the town of Fort William.

The Mission de L’Immaculée Conception was modelled on the Jesuit Holy Cross Mission at Wikwemikong, also founded by Father Choné in 1844 for the approximately 800 Catholic Indian people living on Manitoulin Island. At both missions a Jesuit residence, a church, an orphanage or school, a farm, and a cemetery were the basic structures around which religious and social life turned. Moreover, there was an on-going exchange of personnel between the two missions depending on the needs of each and the health of the missionaries involved. In the summer of 1892 for example, the Jesuit provincial informed the Most Rev. Richard O’Connor (1838-1913), Bishop of Peterborough, of a personnel change affecting both missions. “Fr. Baudin is strong and would desire more work than he has at Fort William,” wrote the Jesuit provincial. “On the other side Fr. Hébert’s health is not good and Fort William would be a better place for him because there is little to do.”

Since its inception and notwithstanding the lighter workload at the Fort William Mission, at least three Jesuits had been assigned to the Mission de L’Immaculée Conception thus providing the canonical requisite for a religious community. A careful examination of the biographical details of the Jesuits who had served at the Fort William Mission during the 1870s and 1880s prompted historian Elizabeth Arthur to comment on their “extraordinary experience and talent.” In varying degrees, each had established an exemplary record as a missionary in northern Ontario prior to their arrival at the Fort William Mission. Several not only mastered the Ojibway language but were recognized as Ojibwa scholars throughout North America. Father Alphonse Baudin (1833-1909) for example, Jesuit Superior at the Fort William Mission (1891-1892; 1897-1901), was a gifted linguist. He translated into Ojibway the Gospels and Acts of the Apostles, the Baltimore Catechism and the French-Ojibway Dialogues. Father William Gagnieur (1857-1937) succeeded Baudin as Superior (1893-1895). By the time he had arrived at the Fort William Mission, his list of publications on the language, culture and history of the North American aboriginal people was so impressive that the University of Michigan conferred on him an honorary L.L.D. While Joseph Hébert, Alphonse Baudin and William Gagnieur, as Superiors, tended to the religious and administrative affairs of the Fort William Mission proper, it was usually their assistants who traversed the vast frontier of the Canadian Shield north of Lake Superior to establish new missions and to minister to the Ojibwa people. Whether it was the seventeenth century in their contacts with the Huron or the nineteenth century in their associations with the Ojibwa, the relationship between language and culture and the Jesuit “way of proceeding” among aboriginal peoples remained the same: mastery of their language and a knowledge of their culture was essential in persuading them to become Christians.

The construction of a Roman Catholic Church in Fort William coincided with the incorporation of the town in 1892. The initiative originated with the people. Given the crowded conditions at the Church of the Immaculate Conception on Sundays, Father Alphonse Baudin, s.j., Superior at the Fort William Mission, believed a church in "Fort William East" could be built without much difficulty. A notice appeared in the Fort William Journal inviting all persons interested in creating a Roman Catholic Church to meet at McDougall's hall on Sunday, 8 September 1891 at 2:30 p.m. Out of this meeting, attended by twenty-five individuals, a church committee was formed headed by a prominent businessman, James Murphy. In addition to collecting pledges totalling $560, the committee identified the city lot upon which a church, school, and convent would be built. Within ten days of the organizational meeting, the committee called for tenders to lay the foundations and to construct the church based on plans and specifications drawn up by a prominent local architect and businessman W. R. Graham.

By June 1892, construction had begun at the corner of Donald and Archibald streets under the direction of a Mr. H. Rochon. “When the church is completed,” reported the Fort William Journal, “it will be one of the most handsome edifices in town...” In the yet unfinished 40’ x 80’ frame church, with a sacristy built on the side, the first mass was celebrated on 21 August 1892 before a large congregation by Father Remi Chartier, s.j., (1839-1906) Superior of the Jesuits in the Thunder Bay District and pastor at St. Andrew’s in Port Arthur. There was a saying among St. Patrick parishioners at the time concerning their first church: “The French built it, and the Irish named it.” A year later, during his pastoral visit to Fort William, Bishop O’Connor formally established a parish under the patronage of St. Patrick and announced to an expectant crowd that a stained glass portrait of St. Patrick would be positioned over the main altar and that a resident priest would remain in their midst.

That priest was Father Ludger (Roger) Arpin, s.j. (1841-1918). Father Arpin was born in La Presentation in the Diocese of Saint-Hyacinthe, Que., on 10 April 1841.At the age of 22 he entered the Society of Jesus at Recollect Falls. His formation as a Jesuit included studies in Quebec City, Fordham University, New York and at Woodstock, Maryland, USA. He was ordained on 9 September 1877 and took his solemn vows at St. Mary’s College, Montreal, on 15 August 1882. His initiation to fund-raising and building institutions began in 1885 when he became involved in the founding of the College of the Immaculate Conception in Montreal. Shortly thereafter, he spent a brief period (1890-1893) as Superior of the Jesuit community in Sault Ste Marie and then moved further north as the first pastor of St. Patrick’s parish in Fort William. For the next thirteen years he provided leadership and a vision for a Roman Catholic community in what was still a frontier town in northwestern Ontario.

One of Father Arpin’s first priorities as pastor was to have a Roman Catholic elementary school built in the city. The parishioners at St. Patrick’s, however, were reluctant to follow his lead. To build the school meant increasing their property taxes. For some, the financial commitment to their church was already stretched to the limit as they contributed to the completion of the church and rectory in 1893. Others felt that the creation of a Catholic elementary school in Fort William would create tensions between Roman Catholics and Protestants in the community. The more affluent parishioners were concerned that a separate Roman Catholic school would not provide the quality of education found in the public system. A divided parish on this issue left the “school fund” dormant and postponed action on property acquisition and construction. Father Arpin was understandably frustrated. “...If God sends me good luck, I may have the means to build a first class school,” he wrote. “My people are very proud; they want everything fine, but they cannot, they say, pay for it.”

But Father Arpin was persistent. In the spring of 1901 he became involved in the formation of a Separate School Board for the town of Fort William. Notice was given of a public meeting of Roman Catholics families to be held in the basement hall of St. Patrick’s Church on 10 April. After a motion that the Roman Catholics assembled wished to form a Separate School Board for Fort William was passed, two trustees from each of the four wards in the city were nominated and elected. Father Arpin was elected a trustee for Ward IV. At a subsequent meeting he was elected Secretary-Treasurer of the newly constituted school board. In this position he reported on the progress of fund-raising for a new Roman Catholic “school house.” In the spring of 1901 he was able to convince his parishioners, with Bishop O’Connor’s encouragement, to launch a subscription campaign for the Catholic elementary school project. Bishop O’Connor honoured his commitment to be the one of the first to make a personal donation to the cause. At a special meeting of the board on 22 May 1901 Arpin informed trustees that $1,500 had been subscribed. On the basis of this commitment, the board struck a committee comprised of Joseph C. McDonald and Father Arpin to consult with local architects and contractors with a view to constructing a school house at a cost not to exceed $10,000 when completed. By the fall of that year, the property had been acquired on Myles Street and construction had begun. “It is going to be a fine looking building...” wrote Father Arpin as construction progressed. “Protestants cannot believe their eyes to look at such a school; they are literally wild, feel bad and blame the priest to have put such a scheme into the catholic heads, whilst our Catholics seem to have more courage than ever.”

St. Stanislaus Roman Catholic School in Fort William situated at 241 Myles Street officially opened its doors on Wednesday, 8 January 1902 to 101 Catholic children who had previously attended the public school. In the space of four weeks that number had risen to 130. Father Arpin took great satisfaction in knowing that few Roman Catholic children remained within the Fort William public school. As a four room, two-story all brick structure it had already been filled to capacity. At the request of Bishop O’Connor five Sisters of St. Joseph (Mother St. Edward, Sisters Magdalen, Fidelis, St. Catherine and St. Philip) agreed to staff the school. That the Sisters of St. Joseph would bring the highest standards of instruction to the school was an assurance Bishop O’Connor confidently gave to Father Arpin and his parishioners. “Wherever the Sisters of St. Joseph have charge of schools,” he wrote, “we find that their pupils are taught the secular branches in as satisfactory a manner as the pupils in public schools, and besides the children are well rounded in the knowledge and practise of their religion, a matter that is of the greatest importance...” For their part, the Sisters of St. Joseph, operating from their temporary living quarters on the second floor of the school, candidly informed the Bishop of Peterborough of their impressions of the new school and the pupils in their charge. Bright classrooms, hardwood floors throughout, running water, electricity and hot air furnaces were more than they ever expected. Although their students were not “unruly” as they were led to believe they would be, they found them wanting in basic academic skills. Accordingly, preparation for high school entrance examinations did not take place in 1902. Nevertheless, Roman Catholic elementary education had begun in Fort William. Father Arpin and St. Patrick’s parish were the prime movers in this development…

St. Patrick’s parish, under the leadership of their pastor Father Arpin, provided the catalyst for the development of Roman Catholic institutions in Fort William at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Fort William Separate School Board, St. Stanislaus School, St. Patrick’s Cemetery and the Sisters of St. Joseph Convent on Myles Street all found their origins with this parish. Little would have been accomplished, however, without the vision and risk-taking of Father Arpin. St. Patrick’s became the parish around which first and second generation Polish, Slovak, and Italian immigrants rallied. Father Arpin was a source of encouragement to each cultural group to practise their faith within the context of an Anglo-Saxon and French-Canadian dominated parish. For example, he assisted the Slovaks in bringing in a priest from Pennsylvania who spoke their language to give a six-day mission during the Lenten season of 1900. He delighted in the satisfaction and joy they took in hearing sermons in their own language and in socializing among themselves. He also purchased several lots in Fort William’s East End, knowing that the Slovaks eventually would want to build a church of their own in that part of the city. The Sisters of St Joseph Convent which opened in 1905 across the street from St. Stanislaus School on Myles Street also owed its existence to Arpin’s initiatives. He purchased five lots on which it was built for $2,000 and the construction cost of $13,000 was borrowed by St. Patrick’s parish on the security of Diocese of Sault Ste Marie. As long as the Sisters of St. Joseph staffed St Stanislaus School, they resided at the convent rent-free and its maintenance became the responsibility of St. Patrick’s Parish.

As a tribute to Father Arpin, St. Patrick Parish under the leadership of Father Patrick J. Monahan (later to become the Bishop of Calgary), financed the construction of the only private Roman Catholic high school in northwestern Ontario which was officially opened on 21 November 1928 at 205 Franklin Street South, Thunder Bay. Since some of the funds for its construction came from the estate of Father Arpin, the school was appropriately named St. Patrick Arpin Memorial High School. From 1928 until the mid-1960s, St. Patrick Parish shouldered the entire cost of its operation and administration. With these institutions in place, Fort William’s Roman Catholic community was able to grow and flourish